The Tahbilk vine trunks are sturdy and impressively knotted. They don’t mind putting on a show, after all, they are among the most photographed grape vines in the country. Admittedly, they’re not getting any younger and not all of them remain, there are empty spaces to announce the odd death, but with the 2025 vintage only months away they are looking pretty perky. These shiraz vines, some of the oldest in Australia, were planted in 1860 and they line the entry to Tahbilk vineyard (it's an impressive welcoming party to visitors). The 1860 vines remain a constant, super resilient, seemingly oblivious to time. It’s a fitting metaphor for the Purbrick family.

The Purbrick family owns Tahbilk. And while its origins date back to 1860, this year, the Nagambie Lakes vineyard celebrates 100 years of Purbrick ownership. However, in the mind of Alister Purbrick, fourth generation and chief executive, and his family, there is the traditional western concept of ownership and then there is custodianship.

“Essentially the ownership of Tahbilk Estate is locked away,” he says. “It can’t be sold.” The creation of a number of legal agreements, including a family constitution and family council, now ensures Tahbilk will remain in family hands for many more generations. That, he says, means each generation can work towards – borrowing a phrase from his grandfather, the late Eric Purbrick – “continuous improvement”.

For fifth generation Hayley Purbrick, that means looking to the natural environment as much as wine. The phrase is a statement about what is possible not only in wine, but in preserving the land. What was once a mixture of broadacre farming and vines is now devoted to wetlands across 1214 hectares of wildlife reserve, including eight kilometres of lagoons and anabranches of the Goulburn River and wildlife corridors. The winery runs on solar and has been accredited as a carbon neutral producer since 2013. Which leaves the wine.

Tradition runs strong at Tahbilk. It goes hand-in-hand with the site – the old underground cellars and the original 1860 winery housed in a low-slung French chateau-style building. Not to mention the producer just about owns the marsanne category in Australia – a fact that continues to surprise Alister Purbrick.

“It really serves us well that not too many producers have embraced the variety, for whatever reason that might be, because that has left it pretty much open to us,” he says.

The Rhône grape is one versatile performer and the makers are open to interpreting its delightful honeysuckle aromatics and citrus in any number of ways. There's the sparkling, the young and fresh expression, and then there's something a little more ageworthy – it's not uncommon for marsanne to be aged for 15–20 years – and let's not forget the sweeter and dessert styles. Originally planted in 1860, the advent of phylloxera in the early 1880s saw the first marsanne vines perish.

“But for reasons that Grandfather could never explain to me,” says Alister, “he decided that they were going to replant marsanne, which are the 1927 vines. Perhaps it was a nostalgic thing.”

The red grape most associated with Tahbilk is shiraz. It was planted in 1860 by a Burgundy-trained winemaker, Ludovic Marie, who saw a connection between the land, the climate and, not Burgundy, but the Rhône Valley.

But how do you keep ancient vines going?

“It’s up them,” comes the reply from Alister Purbrick. “Floods are not going to destroy them,” he's referring to the flooding in late 2022 that saw the vines completely submerged. The biggest danger is frost. “The frost analogy for me is, think of an elderly parent or relative in their 90s. They’re going along beautifully, and then all of a sudden something comes out of left field, they slip in a bath and break something. And a lot of times it’s just too much for them. That’s what the really severe frosts do to the old vines.”

In 2006, a -6ºC frost event saw 20 per cent of the 1860 shiraz plantings die. “I think we're down to 50–55 per cent of the area that still has vines,” he says. The ones that are surviving are genetically stronger and they yield quite well. “Sometimes they get a bit too vigorous and we have to take a bit of crop off, would you believe?” he laughs. The Tahbilk shiraz clone – it is so old it has its own name – originally came from Hermitage in the Rhône Valley, boasts small berries, produces strongly coloured wines, good acidity and given the lighter, sandier soils of Tahbilk there is a finer, quite elegant expression achieved.

It’s a similar story with the cabernet sauvignon which, according to Alister Purbrick, is often every bit as exciting and consistent as shiraz but just hasn’t captured the imagination of drinkers nearly as well. “I think we do cabernet here, now, better from a quality perspective than we do shiraz.” A slowly warming climate has helped, particularly with ripeness levels.

“That little bit of extra heat at the end of the growing season just gets them over the line, whereas in my earlier days here we got caught with cabernet where we could hardly get it through. So, you have to pick them a bit greener or earlier. “Apart from Mother Nature and wet events, we’ve had a remarkable run of cabernet since the mid '90s.”

Wines under the Tahbilk label will stay 100 per cent estate grown and made. “That is set in stone,” says Alister. “Then, it is a matter of experimenting.” Grenache is planted but essentially restricted to blends. “They’re pretty vigorous vines and I reckon they’ve got to be at least 100 years old before they devigorate to an extent where you get much lower crops, smaller berries.”

Viognier, another Rhône specialist, has proven its worth and works well. Trends come and go, at Tahbilk some resonate more than others. In the ground now is montepulciano. Whether it progresses further will be up to testing by wine club members.

The lure of good wine is strong at Tahbilk, but so, too, is the tranquility of a natural beauty restored. Wetlands trimmed in a green carpet of Monet-esque native water lilies are home to black swans, pelicans, ducks, hundreds of birds and species of wildlife, some endangered. Wildlife and eco trails abound taking you deep into the country and the story of the Indigenous ancestral owners of the land, the Taungurung. It sits well, in harmony, with the vines and the wines of Tahbilk’s latter day co-custodians, the Purbricks.

100 years of Tahbilk

1925: Englishman Reginald Purbrick purchases Tahbilk and sends his son, Eric, to Australia to restore the estate. Eric is followed by his son, John.

1978: Fourth generation Alister Purbrick starts as winemaker.

1979: A 300-tonne white winemaking facility is built separate to the old red wine winery, keeping the integrity of the original 1860 buildings intact.

1991: Eric Purbrick passes away.

1995: First revegetation project gets underway. In total, 150ha of land has been revegetated. Another 100ha will be revegetated by 2030.

2009: Tahbilk becomes a founding member of Australia’s First Families of Wine formed by 10 of Australia’s oldest family-owned, multi-generational wine companies.

2013: After starting its carbon neutral journey in 2008, Tahbilk gains its first carbon neutral certification.

2016: Tahbilk is named Halliday Wine Companion's Winery of the Year.

2018: Solar power debuts at Tahbilk. With further installations, Tahbilk will generate over one third of its annual energy requirements from the sun.

2023: Taungurung leaders share their knowledge of country, guiding visitors on walks across the Tahbilk wetlands.

Track your wines with your personal Halliday Virtual Cellar

The Halliday Virtual Cellar is a cellar management tool that tracks your wine collection with ease.

Using the Virtual Cellar, you can save wines directly from the Halliday Wine Companion site, create entries for wines the Tasting Team haven't yet tasted, and create wishlists for those wines you've been eyeing off. You can also add personal ratings and tasting notes, and export your collection to an Excel document. What better way to track your Halliday Wine Club wines?

Halliday members receive exclusive access to the Virtual Cellar. Become a member to start adding to your virtual cellar now.

Latest Articles

-

![Default article tile image]()

News

Does the Adelaide Hills have an image problem?

2 days ago -

![Default article tile image]()

From the tasting team

Sustainable and beyond: Marcus Ellis on sustainability in the wine industry

2 days ago -

![Default article tile image]()

News

The reinvention of the Aussie sommelier

2 days ago -

News

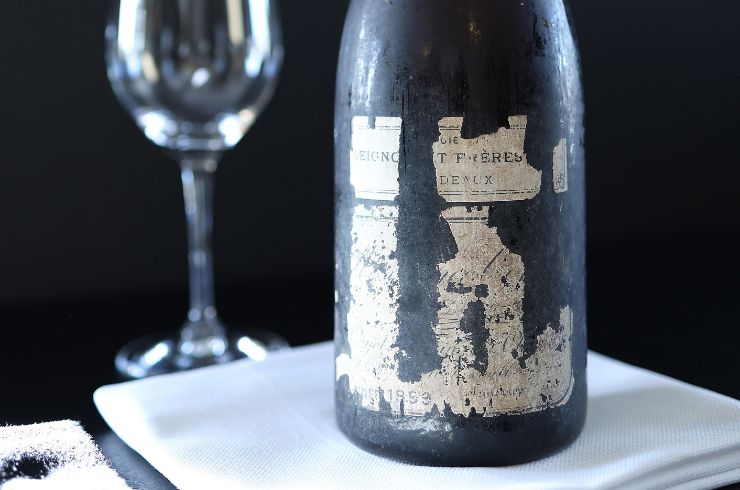

Why a co-owner of Bass Phillip decided to taste, instead of trade, this 127-year-old bottle of wine

2 days ago