“In Australia, everyone thinks riesling is going to be dry,” says Jane Lopes, California-born, Tennessee-based co-founder of Legend Australian Wine Imports. “And everyone pretty much wants a dry riesling, too. Or at least...they think they do.”

Jane, who spent three years as wine director for acclaimed Melbourne restaurant Attica, says the opposite is true in the US. “It’s still a surprise for most American consumers that a dry riesling exists,” she says.

The tasting menu at Attica kicks off with 10 snacks, which Jane would pair with two rieslings – usually an Australian or New Zealand next to a European example. She says most people expected to prefer the dry riesling, but it was the wine with a little residual sugar that blew people away. “We had trouble keeping people’s glasses full!” she says.

Riesling is not the only white grape that lends itself to sweetness – chenin blanc and pinot gris come to mind – but it’s one of the best, due to its tendency to ripen late; the extra hang time helps to build sugar without losing natural acidity. The sugar in wine is different to the sugar in soft drink or desserts, though. Residual sugar is grape sugar not converted to alcohol during fermentation. Many dry wines also have residual sugar with no obvious sweetness – brut champagne, for example, can hit 12 grams per litre and still taste dry.

One local producer who has truly embraced the dry-to-sweet spectrum of riesling is John Hughes of South Australia’s Rieslingfreak. He makes 11 expressions – and counting. “We make a traditional method sparkling, a fortified, we do dry riesling and we do sweet. There aren’t many grape varieties in the world you can do that with,” he says.

John grew up on the family vineyard in Clare Valley before heading off to university, where a love of riesling earned him the nickname “riesling freak”. The moniker has adorned his labels since 2009 – fitting, as he doesn’t work with any other grapes.

John uses a non-sequential numbering system for his wines. The inaugural No. 1 Riesling wasn’t released until 2017. “I wanted to design a barrel to ferment the wine in, and that takes a lot of time and money,” he says. It’s $100 a bottle, only made in the best years and the fruit is hand-picked and wild fermented. The best-selling No. 3 is most typical of South Australia’s dry riesling style, with typical racy acidity and citrus tang, however John says the No. 5, an off-dry riesling, is hot on its heels in terms of popularity. “It’s only 13 grams [of residual sugar], but people don’t perceive it to be sweet,” John says.

Despite the abstract numbering, the Rieslingfreak wines are easy to figure out. Like a growing number of winemakers, he uses the International Riesling Foundation (IRF) infographic on his back labels. “The IRF scale shows the wines from dry to sweet – we have a little arrow to identify where it sits in terms of style,”

he says.

On the other hand, Geelong-based winemaker Sierra Reed of Reed Wines isn’t interested in bone-dry rieslings. “If you have high-acid fruit and you make that wine really dry, then it’s going to be severe,” she says.

Sierra’s White Heart Riesling is one of three Australian rieslings that Jane imports for the US market. The 2019 vintage had 23 grams of residual sugar, the 2020 vintage had six grams, and the 2021 came in at 18. Sierra sells them all as table wines.

“The acid does the work to pull the sugar across,” she says, careful to stipulate that she means natural acid, not the tartaric acid that may be added to wines in Australia. “Everything for me is about balance.”

Sierra wants people to push past their preconceived notions about off-dry wines. If there’s acid for the sugar, the numbers don’t matter, she says. “It gives you another sense...it’s not just taste, it’s physical.”

In the Canberra District, Ken Helm of Helm Wines has been making wine for 45 years. “The first wine we ever made here was a riesling, and that was in 1977,” he says. But longevity is not his greatest claim to fame. Not only did Ken establish the Canberra International Riesling Festival, which now attracts 500 entries from 10 countries, but he was also instrumental in changing the legal definition of the grape. “In 2000, we lobbied federal parliament to have the word ‘riesling’ be exclusively for the riesling grape,” he says. “Prior to that, you could put anything in a bottle, bag or box and call it riesling.”

Eight years ago, Ken built a second winery just for riesling wines (his accountant calls it an indulgence, but we respectfully disagree). He got the idea in Germany, where he regularly travels to judge wine shows – here, names like Joh Jos Prüm and Dr Loosen have been making riesling, sometimes only riesling, for generations. “Our wines have benefited from that extra attention to detail, too,” Ken says.

Cool summers and long, sunny autumns make Tasmania a stellar riesling-producing region, although its winemakers forge their own way. Moorilla Estate winemaker Conor van der Reest and Laurel Bank/Quiet Mutiny winemaker Greer Carland make strikingly different rieslings out of their Derwent River wineries, despite being only kilometres apart.

Established in the 1950s, Moorilla’s southern vineyard, which you’ve walked past if you’ve been to MONA, is home to Tasmania’s oldest riesling plantings. Due to its proximity to the river, that fruit attracts botrytis, a tricky yet beneficial fungus that brings nectar-like flavours to a wine. A second vineyard site, St Matthias, near Launceston, is also planted to riesling, turning out grapes with strong apple and lime notes. Unfortunately, neither vineyard was a good fit for the kind of wine that people really wanted to drink in the early 2000s.

We were trying to emulate the South Australian style of crisp, fruity, dry wines. They’re amazing, but it just wasn’t a style our vineyards could do,” Conor says. When he took the reins in 2007, there were pallets of perfectly good riesling languishing in storage. “I wasn’t worried about how it would age, but I was worried about selling it!” he says.

The solution? To switch things up with two completely new wines. First up was a sparkling riesling inspired by Sekt, Germany’s beloved sparkling style, released under the Praxis label. It was the perfect fit for St Matthias’ northern Tasmanian grapes, and now he can’t make enough of it.

With that problem solved, Conor turned his attention to the Derwent Valley site – and its noble rot. It took eight years to get right, but he says the change made life a lot easier. “We’re not fighting against something; we’re working with it.” The Muse Single Vineyard Riesling is still dry, but with plenty of fleshy, ripe flavours from 10, maybe 20, per cent botrytis-affected fruit and lots of texture from barrel ageing.

Further back from the river’s edge – although not by much – Greer is winemaker at family label Laurel Bank and Quiet Mutiny, a solo project she launched in 2017. “Dad [Kerry Carland] looks after the vineyard, and I’m the boss of the winemaking,” she says of their small Granton-based winery, which has two blocks planted to riesling.

The recipe for the Laurel Bank is set in stone. “It’s that classic Australian dry style – it’s clean and fresh, and we don’t mess around with it,” Greer says. But the Quiet Mutiny Charlotte’s Elusion Riesling, named for Charlotte Badger, Australia’s first female pirate, is an entirely different story.

“People either think riesling is too sour, that it’ll make them cry, or they think it’s going to be too sweet. I wanted to make a wine that was inclusive – still distinctively riesling, but more approachable,” she says.

The Quiet Mutiny riesling is made from the same blocks as the Laurel Bank, although percentages vary based on vintage. The main difference is in the winemaking, particularly skin contact for the Quiet Mutiny, which gives a musky, floral aroma. Greer calls it a “restaurant wine” because its texture and aromatics make it food-friendly in a way that some bone-dry, high-acid rieslings are not.

“I just made a wine I wanted to drink,” she says. “When you start a label, you’re never quite sure how many people are going to buy the wine, so it’s a good failsafe to make something you actually like.”

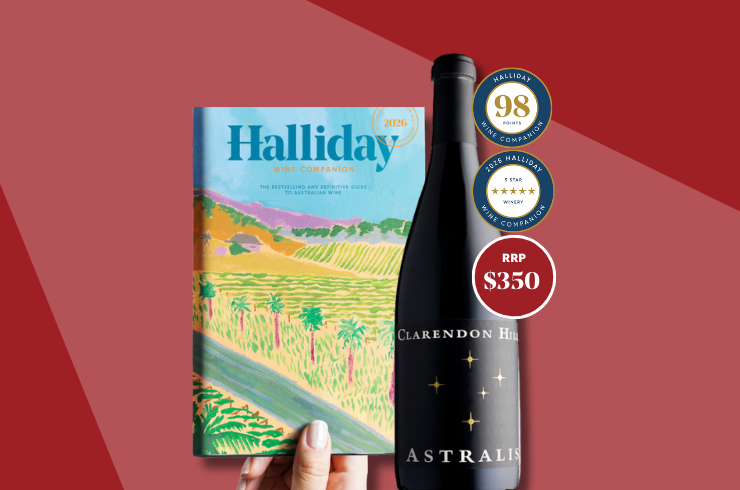

This article first appeared in Halliday magazine. Become a member to receive the print publication as well as digital access.

Latest Articles

-

Wine Lists

italian-varietal-wines

18 hours ago -

News

Back-vintage tastings, cellar tours, degustations – why you should go to Tastes of Rutherglen this March

1 day ago -

News

The history of Seppeltsfield's treasured 100 Year Old Para Vintage Tawny through our favourite tasting notes

1 day ago -

Win

Open That Bottle Night competition: win over $500 worth of prizes

2 days ago