Go to section: Single malt whisky | Rye whisky | Other whisky types | Whisky definitions | Does age matter in whisky?

Single malt whisky

Single malt whisky, by definition, must be produced at a single distilling facility from 100 per cent malted barley. Australian single malt whisky is arguably the most influential category of locally produced spirits. The distillery that kicked off the modern craft distilling boom (which led to the re-establishment of commercial-scale distilling in Australia) was Lark, in Tasmania, which still makes single malt whisky to this day.

There are now hundreds of distilleries, both large and small, producing single malt whisky in Australia. We are a major global producer of barley – the grain required for single malt – so the primary ingredient for this style of whisky is both abundant and very high quality. Australia also has the advantage of a wonderful wine industry, and many whisky makers rely heavily on ex-wine casks, especially storied fortified wines like apera, tawny and muscat from local producers such as McWilliams, Seppeltsfield and Morris, to lend their whisky a uniquely Aussie character.

By our reckoning, Australian single malt whisky can be broken into two broad classes: old school and new school. Much like many longstanding Aussie wine producers, old-school Aussie single malts tend to follow a European blueprint (in this case single malt Scotch) without a lot of critical thinking about the why or how, lovingly recreating the flavours we know from our culturally close Scottish cousins. The new school, on the other hand (again, like our forward-looking wine producers), tend to focus much more on how Australia’s climate, locally grown grains and available casks result in uniquely Australian whiskies.

The distinction is more about production choices than how long a distillery has existed. Long standing distilleries like Hellyer’s Road and Belgrove take a more modern approach, while newer distilleries like Highwayman still follow the tried-and-true formula.

Old-school Aussie whiskies: Distilleries such as Lark, Timboon, Overeem and Black Gate fall into this old-school whisky category, and are typified by reliance on small-format Australian fortified wine casks filled with a bold, oily spirit. Often delicious, but frequently overpowered by cask influence, these whiskies are absolute flavour bombs, and unmistakably Aussie despite their Scottish inspiration. Old school Aussie single malts also include distilleries like Bakery Hill – which imports peated (peat-smoked) barley from Scotland to distill locally – producing Australian whiskies with a Scottish-style smokiness.

New-school whiskies: Starward, Archie Rose, Cape Byron and Kinglake are good examples of new-school whisky distilleries, for they tend to lean more on larger-format Australian red wine, white wine, and ex-bourbon casks – aiming for a balance between cask and spirit influence. They also tend to focus more on upstream raw ingredients, using tailor-made local malts, specific yeast strains for fermentation, and experimentation with native timbers for smoking and maturing. But these are very broad strokes, with plenty of producers employing both old-school and new-school techniques, meaning the variety and creativity of Australian single malt whisky right now is astounding.

Among both old and new-school Aussie single malts, there are examples of both outstanding and not-so-great products on the market. And while prices tend to be high and quality variable, it’s important to remember that the Australian whisky industry (at least in its modern incarnation) is barely 30 years old, and has only existed beyond cottage scale for less than 15. As global inflation and demand for imported whiskies drive prices up and quality down, while increasing local experience, volume and investment push prices down and quality up among Aussie whiskies, there’s never been a better time to drink local single malt.

Rye whisky

Rye whisky is known in America as bourbon’s older, less famous sibling, produced from rye grain as the name would imply. Rye is drier, spicier and more fruity in flavour than the corn that most bourbon is produced from, producing a whisky that tends to be more complex, though less easy-drinking, than bourbon, and that can hold up to long term maturation whereas bourbon might fall over. There’s also no geographical restrictions on the term ‘rye’ – unlike there are with ‘bourbon’ – so you can make rye whisky anywhere in the world.

While rye whisky was probably the first grain alcohol produced in the US – by early Northern European settlers who had experience distilling rye in the old country – and was hugely popular until the early 20th century, it fell out of favour in the post-Prohibition years. Rye has only gone through a revival in recent years, largely thanks to the resurgence of classic cocktail culture, with historic brands restored and many new ones emerging.

Here in Australia, the vast majority of whisky distilleries make Scottish-style malt whisky, which makes sense given our cultural heritage and large-scale barley production. But we actually grow a fair amount of rye grain here as well, usually as a cover crop, so there are a handful of intrepid Australian distilleries now producing Aussie rye whisky with incredible results.

The first was Belgrove Distillery, the passion project of one of Tasmania’s original whisky pioneers, Peter Bignell, who hand-built his distillery from scratch to make use of an excess of rye grain he’d grown to feed his sheep. Peter was doing grain-to-glass whisky production way before it was cool, and his hand-crafted batches of Tasmanian rye taste nothing like the commercial-scale American stuff. But good luck getting hold of a bottle.

Back on the mainland, Melbourne’s The Gospel has built a small-by-American-standards but still commercial-scale operation based entirely on Australian rye. Inspired by classic American styles yet also 100 per cent Aussie, their rye is sourced exclusively from northwest Victoria’s arid Mallee region, and rye whisky is the only product they make. Unlike Bignell’s back-shed operation, The Gospel wants to see Aussie-made rye replace the imported stuff on every bar and cocktail list in Australia. With consistent, reasonably priced whisky, and strong marketing, they’re getting there, and are even exporting to rye’s homeland in the US.

Sydney’s Archie Rose also produces a hugely popular rye malt whisky made from softer, sweeter malted rye that sort of bridges the gap between single malt and rye whiskies, working with craft maltster Voyager in western NSW to revive heirloom varieties of Aussie rye grain for their whiskies. Archie Rose Rye Malt won World’s Best Rye at the World Whiskies Awards a few years back – only the second Australian distillery (after Sullivans Cove) to pull a ‘World’s Best’ title from that hallowed competition, so it seems like they’re doing something right.

Smaller craft distilleries on the mainland, like Victoria’s Backwoods and WA’s Great Southern Distilling Company, have also produced rye whiskies, but it’s precious few compared to the profusion of local single malts available. Rye grain expresses its terroir much better than barley, and it’s also way more drought tolerant, so it makes a lot of sense for Australia to lean into a style that both expresses and protects our landscape. So here’s hoping more Aussie rye whisky hits the market in coming years as a style that’s ripe for harvest.

Other whisky types

There are only a handful of whiskies made in Australia that don’t fall under the definition of ‘single malt’ or ‘rye’, but that’s changing, so here are a few you can expect to see kicking around the Australian craft spirits market:

Blended malt whisky: When single malt whiskies from multiple distilleries are blended together, this is known as ‘blended malt’ – still made from 100 per cent malted barley, but with multiple distilleries involved. Lark Symphony is a good local example, whereas Monkey Shoulder is an example of a blended malt from Scotland.

Blended whisky: When single malt whisky is blended with lighter, more industrially produced wheat or corn whiskies, this is known as ‘blended whisky’. Imported versions are easy to recognise as the world’s most famous Scotches like Johnny Walker, Dewar’s and Chivas Regal. Local versions like Starward Two Fold and Archie Rose Double Malt are only just starting to hit the market in Australia, providing consistent, low-cost local whisky for the first time. Watch out for many more of these to hit the market in coming years.

Bourbon-style whiskies: sometimes referred to as corn whisky, bourbon-style whiskies are produced by a handful of Australian distilleries like Great Southern Distilling Company and NED. The problem is, we can’t call them ‘bourbon’ because that’s a term reserved by international trade agreement for American-produced corn whisky. Aussies LOVE bourbon, consuming more per capita than most countries in the world, so it’s a shame the marketing of local corn-based whiskies is so tough. And much like it took us a while to learn that local sparkling wine can be just as good as Champagne, it’s a long road to get Aussies to drink local not-bourbon, especially when the imported stuff is still cheap compared to Scotch or local whiskies.

Irish-style whiskeys: also called ‘pure pot still’ or ‘single pot still’, these are local whiskies made in the traditional Irish style. Of course, anything that’s made here can’t be called Irish, but considering the many, many Irish forebears of the Australian population, it makes cultural sense that we’d try to do a local version of the Emerald Isle’s native whiskey (spelled with an ‘e’ in that great nation). Generally made on a pot still (like single malt), but with a combination of malted and unmalted barley and sometimes oats, Irish-style whiskeys usually have a lighter, grassier, more grain-forward palate than single malt. Much like bourbon-style whisky, there are only a handful of distilleries attempting an Irish style locally, but Tasmanian brands Transportation Whiskey and Hunter Island as well as Tara Distillery in NSW are giving it a real crack.

Single grain whisky: This is a confusing term, because it does not mean that only one type of grain is used, in fact often the opposite. While the word ‘single’ means it must come from one distilling facility, the fact that it does not say ‘malt’ means that any grain or combination of grains may be used. It’s kind of a catch-all term for anything that’s not made from 100 per cent malted barley. Examples include things like 78 Degrees Australian Whisky, made with a combination of malted and unmalted barley, and alternative grain whiskies like Whipper Snapper’s quinoa whisky. These brands will not use the term ‘single grain’ on their labels, because it’s confusing and more associated with the kind of cheap commercial whisky produced in the UK to make blended whiskies, so in Australia it’s mostly used as a designation for industry-focused spirits competitions. It’s just good to be aware that there are some really cool alternative whiskies on the market here that defy categorisation.

Whisky definitions

Single cask: In short, this means a whisky that has been bottled from a single, individual barrel, not married together with other barrels to create a batch. Most single malts on the market globally, despite being produced at a single distillery, are still made up of many, many casks to create a large batch. In Australia, single-cask single malts tend to be much more common, as it’s often easier for a small distillery to pick the best casks than come up with a well-balanced batch. That’s starting to change, though, as stocks increase and producers gain more experience with bigger batches.

Small batch: This is a meaningless marketing term, generally suggesting a batch of whisky smaller than the largest produced by that brand, so anywhere from one cask to tens of thousands depending on the brand.

Ex-bourbon casks: American oak casks previously used to mature bourbon are the most commonly used casks in the world for maturing single malt whisky. That's because they've already had a lot of the flavour and tannin leached out of them by the bourbon – almost all bourbons are intensely oaky because the barrels are fresh (or ‘virgin’) when that whisky goes in. So after the bourbon has been decanted and bottled, the empty casks go to places like Scotland, Ireland, Japan and here to Australia to be used for maturing single malt and other spirits.

Because so much of the oakiness has already been stripped from these casks, their influence on the whisky is very gentle, offering subtle coconut and vanilla sweetness and a buttery texture. While many Aussie whiskies, other releases from Furneaux included, rely on the heavy sweetness and bold flavour of fortified wine casks, bourbon casks instead offer an unobstructed view of the character of the spirit coming from the stills, leaving nowhere to hide bad technique or rough edges. Bourbon cask whiskies are for people who really like whisky. I often say of the heavily fortified-wine influenced whiskies of the world, why bother when I could just drink a glass of sherry for much cheaper? Bourbon casks also provide a much gentler maturation environment, meaning the spirit can age for much longer without becoming overpowered by the oak.

Does age matter in whisky?

Yes, age matters in whisky. Older doesn’t mean better, necessarily, but it’s still a huge factor in the character of a whisky. Much like wine, young whisky tends to be bright, demonstrative and sometimes a little volatile, while older whiskies tend to be less bombastic but more complex, textural and well-integrated. And like wine, whiskies that age for too long in the wrong casks or conditions can become overly tannic, alcoholic, or just sawdusty and overcooked, losing any vivacity. The difference is that while wine matures in the bottle, whisky matures in the cask only, and is inert once bottled. The size, timber type, char level (or lack thereof) and previous use of the casks used for maturation will all have major influence over the character of the whisky.

In terms of the Australian climate when it comes to maturing whisky, there are several factors at play. Our warm, dry and highly variable climate means that flavour and tannin tends to be extracted from the casks more quickly than in cooler, more stable environments (like Scotland). But anyone who tells you whisky “ages faster” in Australia because of the climate is speaking in half-truths, because extraction of flavour isn’t the only thing that’s happening as whisky matures.

Over a long period of time in the cask, the naturally occurring oils and fats present in whisky come together to form longer molecular chains, giving the whisky increased viscosity and texture over the years. There are also oxidative and evaporative forces at work, as well as the filtration provided by the charred inside-surface of the barrel, that serve to decrease volatility and create balance and integration.

In Australia’s dry climate, whisky tends to increase in percentage of alcohol during maturation, whereas in Scotland, where it’s always damp, ABV goes down over time. One of the most important innovations currently happening in Australian whisky (pioneered by Starward), is entering whisky into the cask at a lower alcohol content at the start of maturation, allowing it to age for longer before turning into rocket fuel. This is the kind of thinking we need to make Australian whisky really shine.

Australian producers are also (finally) moving away from small-format casks. These casks, mostly cut down from standard-sized bourbon (200L) and wine (300L) casks into smaller 100L, 50L and even 20L sizes, were designed to impart a lot of flavour quickly so small distilleries could get products to market and start making a return on investment. The problem is that smaller casks will end up with so much oak influence in a short period of time that the whisky won’t have a chance to mellow, so a lot of young whisky made in this way in Australia is volatile and over-oaked.

And what a waste of good oak! You don’t get 15 20L whisky casks from one 300L wine cask. In fact, it’s often just one, the offcuts of all that beautiful, high quality timber ending up on the scrap heap. I hate to think how many gorgeous 80-year-old tawny casks were wasted in this way. But thankfully, as our whisky industry matures and learns to take a more patient approach, so too does our whisky.

Halliday Spirits is home to a whole host of new spirit reviews and details on Australian distilleries – empowering you to find the best whisky, gin, amaro, brandy and more.

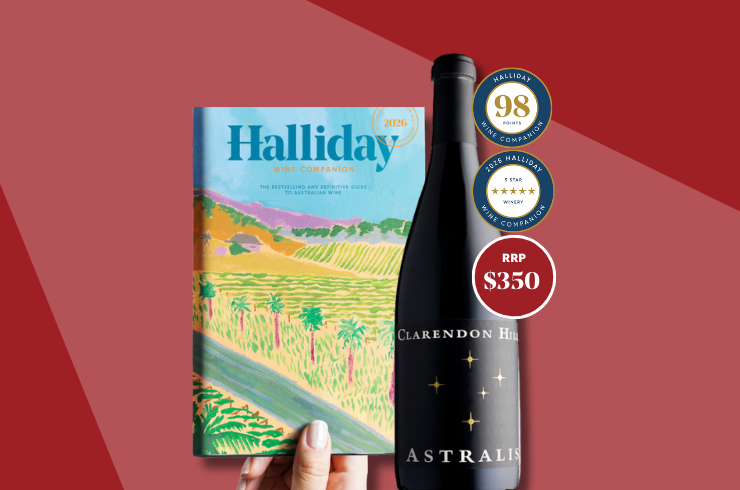

Become a member to get access to all the Halliday wine and spirit reviews

Sign up to become a Halliday member and unlock a wealth of benefits, including:

- Brand new wine and spirit tasting notes delivered to your inbox weekly

- Digital access to our library of over 180,000 tasting notes from over 4000 wineries and distilleries

- Four issues of Halliday magazine delivered to your door per year

- Member-only articles and stories written by Australia's best wine writers

- Early access to Halliday events across Australia

- Discounted Halliday Wine Club subscriptions

- Free shipping on Halliday wine packs

- Member-exclusive offers from our winery, distillery and retail partners

And much, much more. Become a Halliday member today.

Images: Furneaux Distillery courtesy of Tourism Tasmania

Latest Articles

-

Wine Lists

italian-varietal-wines

1 day ago -

News

Back-vintage tastings, cellar tours, degustations – why you should go to Tastes of Rutherglen this March

1 day ago -

News

The history of Seppeltsfield's treasured 100 Year Old Para Vintage Tawny through our favourite tasting notes

1 day ago -

Win

Open That Bottle Night competition: win over $500 worth of prizes

2 days ago